First impressions of Ruby on Rails by a front-end developer

What does happen to the front-end developer who decides to build his first API with Rails? He'll face several roadblocks, I can guarantee.

I have just finished my studies on backend programming and finally released an API built with the most popular framework of the Ruby universe, Rails. If I had to summarize the experience in one sentence, I'd say that learning Rails is like learning to play guitar. Along the never-ending first month, you consider giving up every single day, but getting three chords right in a row is enough to make you believe you have a divine gift.

My intention won't be to write a guide containing the steps to achieve the result I got. A better alternative is to put technical details aside and focus on lowlights & highlights that popped up along the way, avoiding making this article a tedious duplication of tutorials already available elsewhere.

In my projects written in JavaScript, whether on the Browser or Server (Node), I use to create manually all—and only—the necessary files, one by one. I call it Clean Setup. After scaffolding a new Rails project, I counted a pile of files and directories. Curious enough, I visited every directory and file to speculate what they were about. I found empty classes and fully commented files. I didn't delete a single file, of course, but it smelled like the promise we were made at school: you may not need this now, but believe it, this will be useful in the future. Regarding school, I still await usefulness to the calculus I had to learn in chemistry classes. From Rails, I expect a little more compassion.

After getting the project's structure ready, it was time to write the first automated test: creating an user from a payload containing username and password. Then I realize that Rails approaches tests in a way I haven't seen since 2017. A dedicated directory for test files. Although it was not exactly a roadblock, it sounds uncomfortable to me these days having to replicate the existing application directories also inside the directory that contains tests. In my projects built with JavaScript, I place test files inside the same directory where I place the implementation file. Besides saving directories and making access to those files easier, this approach makes it clear that tests are considered first-class citizens in the project.

However, none of the above obstacles can be compared to the act of writing User in a controller and wondering for minutes how Rails knows what that variable means even though I haven't imported any file at all. I'm not sure if it's the way that happens to everybody else, but I got introduced to the auto-loading with the following error: uninitialized constant ApplicationController::JsonWebToken. This was the message that ended up leading me to the explanations I needed so much:

In a normal Ruby program, dependencies need to be loaded by hand … This is not the case in Rails applications, where application classes and modules are just available everywhere. Idiomatic Rails applications only issue require calls to load stuff from their lib directory, the Ruby standard library, Ruby gems, etc.

By default, auto-loading watches the application directory only. To use modules and classes declared outside the application directory (lib directory, for instance), you have to require them manually or add those directories to the auto-loading configuration (a strategy that I opted-in).

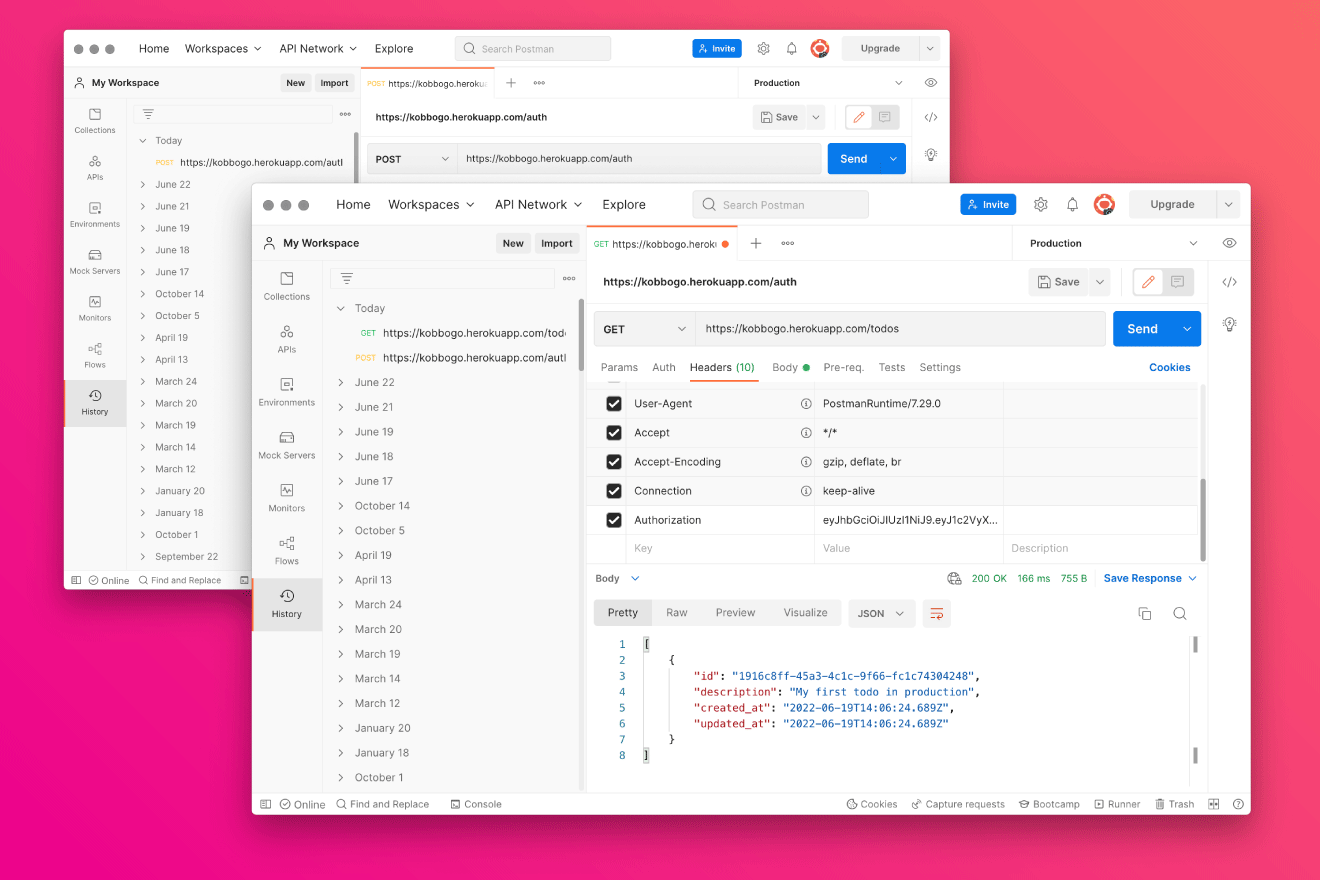

Trying out the API via Postman

But the journey was more than roadblocks. There were also good surprises. To start, I highlight the possibility of pausing the execution of a test at a specific point of the code to inspect its context. Inserting the statement binding.pry (offered by the gem Pry) in any line of my code, I could stop the execution to better understand the state of the variables and the contents present in the error messages.

Another highlight was the power of the gem Rubocop, a library that analyzes code statically, offering suggestions related to code style, complexity, and other topics. After running it for the first time, I got lots of warnings. Most of them regarding style, but one of them surprised me very much. Rubocop was able to detect a missing index in one of the tables of my database, and suggested me to create it, since the column username required unique values.

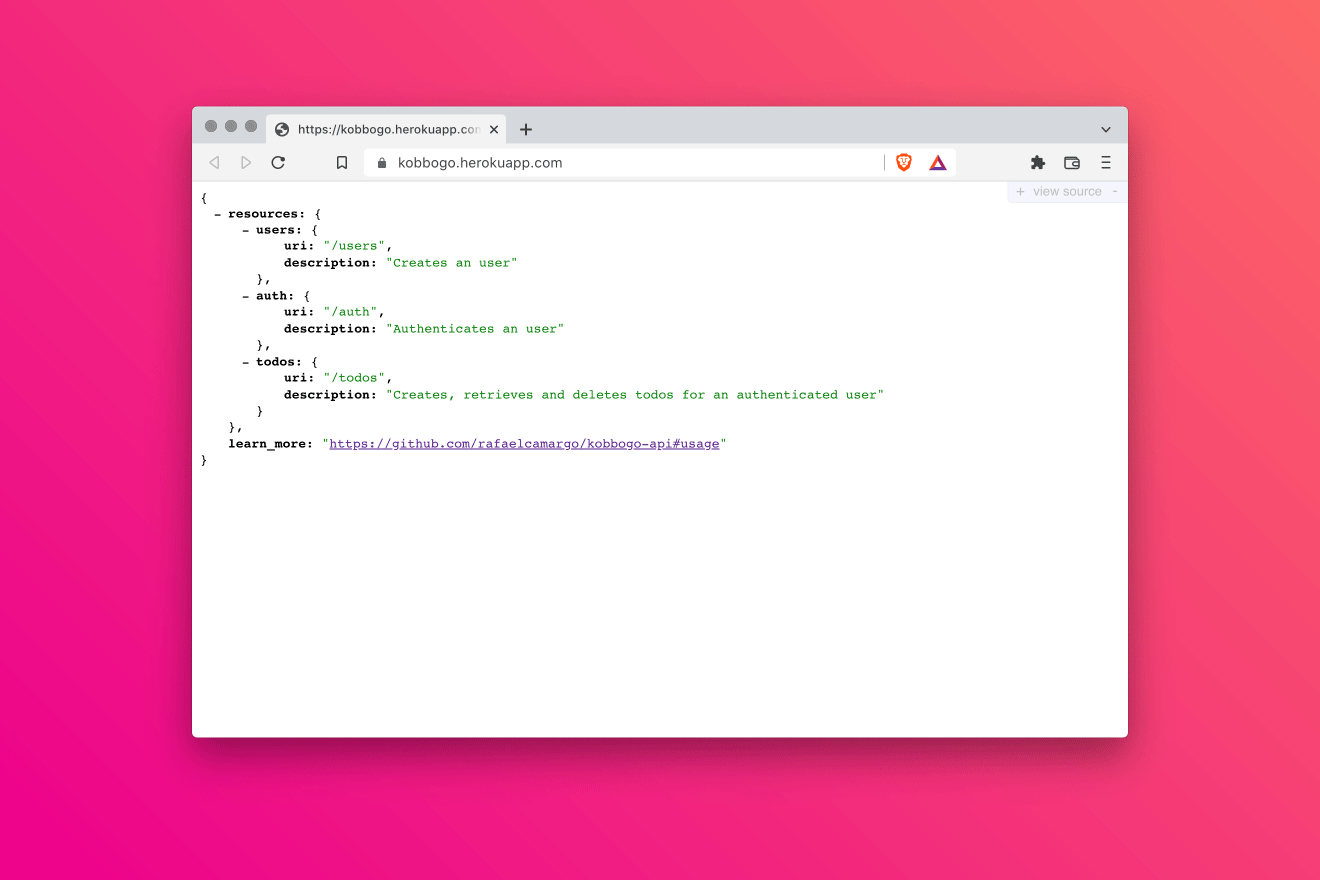

The final highlight was the final step: deploy. I had already used Heroku a few times to deploy projects based on Node, but that didn't need any database. This time I needed PostgreSQL. I was afraid that Heroku would require dozens of additional configurations and demand a tremendous effort from me. Surprisingly, it required me nothing more than a commit to get everything up and running smoothly on its servers, a delightful deployment experience. If you would like to see the API in action, it's available at kobbogo.herokuapp.com*, and its documentation is also available on its repository at Github.

Overview returned by the root path of the API

Below, I share the links that helped me to overcome the barriers. If you are a front-end developer and this story has inspired you, be sure that the links below are the base for you to build your first API too:

- Rest API with Ruby on Rails

- Testing for Beginners

- RSpec Cheat Sheet

- JWT Authentication

- Using UUIDs

- Code Coverage

- Static Code Analyzer

- Continuous Integration: Circle CI

- Continuous Delivery: Heroku

Before finishing this post, I need to thank some developers—workmates and friends—who gave me valuable tips during my journey: Gabriel Escodino, Rodrigo Campos, Almir Mendes, Lucas Cunha and Lucas Merencia. Thank you so much, guys!

*Update: December 12, 2022

From Nov 28, 2022 Heroku stopped to offer Free Dynos. The API is now available on Fly.io through the following URL: https://kobbogo-api.fly.dev/